When Learning Means Letting Go: The Case for Unlearning in Accessible Pedagogy

Reflections on the International Day of Education

Every January 24, the International Day of Education serves as a reminder to pause and reflect on the transformative power of learning. This year’s theme, “The power of youth in co-creating education” (UNESCO, 2026), is particularly timely. As the primary beneficiaries of our educational systems, students have the most at stake in our rapidly changing world. For educators, this theme poses a challenging question: What if some of our most cherished teaching habits are hindering growth and equity?

Educational scholar Erica McWilliam describes long-standing teaching routines as “deadly habits” when they no longer fit a social world marked by complexity, diversity, and constant change. In these conditions, learning alone is not enough. We also require a deliberate practice of unlearning. This involves a willingness to loosen our grip on assumptions about who counts as a “good” learner, what a “proper” clinical encounter looks like, and which bodies and minds are centred as the norm.

Decades ago, futurist Alvin Toffler warned that “the illiterate of the 21st century would not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.” Accessibility work lives in that middle step: the unlearning. It's where we examine which teaching practices create barriers and develop the courage to let them go.

Why Unlearning Matters Now

Universities have long been defined by knowledge acquisition and professional preparation, yet we must remember that education is also a fundamental human right. Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms this right for everyone (United Nations, 1948). Turning that ideal into a lived reality requires more than good intentions. It requires the active removal of systemic, technological, and attitudinal barriers. When educational systems reward rigidity over adaptability, it is not the learners who fall short—it is our pedagogies. As Dalhousie’s Accessibility Plan 2025–2028 makes clear, accessibility is not an optional add-on. It is central to educational excellence.

What Does It Mean to Unlearn?

Unlearning is not about blaming the past, erasing our training, or rejecting the experiences that shaped us. Rather, it means questioning whether the practices that once served us well still serve our current students and the communities they will one day care for. It is an intentional process of identifying and letting go of habits and beliefs that create barriers (McLeod et al., 2020).

Erica McWilliam (2005) notes that teaching habits are useful when conditions are stable, but when the ground shifts, those same habits can become obstacles. At Dalhousie, the ground has indeed shifted. The proportion of students registered with disabilities nearly doubled between 2018 and 2022, growing from 10% to 19% of the student population (Dalhousie University, 2025, p. 5). This is not a marginal shift; it is a structural change. Pedagogical practices designed for the mythical "average" student in a homogeneous classroom—those who process information in standardized ways and experience the world without neurodivergent differences—has reached its expiration date.

Unlearning as an Accessibility Practice

In Academic Ableism, Jay Dolmage (2017) argues that higher education has a long history of treating disability as a problem to be solved rather than a form of human diversity to be valued. Unlearning requires us to stop treating disability as an individual deficit that needs to be "fixed" and start seeing it as the product of social and environmental design choices.

This requires a pivot from a medical model to a social justice model. Individuals are disabled by barriers and norms, not by their bodies alone. In education, the question is no longer, “How do we fix the student who cannot fit into our program?” but rather, “How do we redesign the program so more students can genuinely belong?”

We must also unlearn the assumption that disability is always visible. Mental health disabilities, chronic pain, and neurodivergence remain invisible to observers yet profoundly shape learning. When our only picture of “disabled”* is someone in a wheelchair, we overlook students managing anxiety in group presentations, navigating ADHD during lectures, or coping with chronic fatigue in labs.

Furthermore, unlearning must account for intersectionality. Dalhousie's data reveals that 2SLGBTQIA+ students with disabilities increased from 2% to 6% of the student body between 2018 and 2022 (Dalhousie University, 2025, p. 6). This growth highlights what disability justice advocates have long emphasized: disability does not exist in a vacuum. Students navigate intersecting identities as disabled* and racialized, disabled* and queer, or disabled* and Indigenous. True accessibility requires us to unlearn single axis thinking and embrace these complexities.

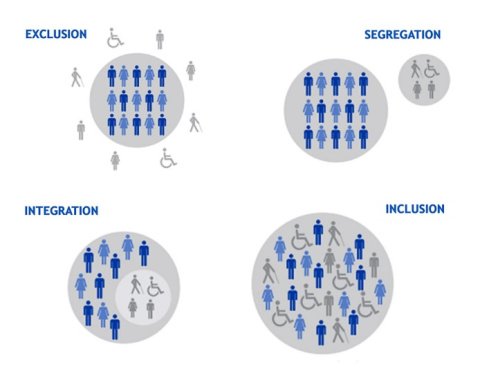

Image from United Nations Office Disability Inclusive Language Guidelines Anex II

Integration versus Inclusion

Across various fields, contemporary thinkers argue that the most future-ready institutions are those that can regularly let go. Entrepreneur Chris Yeh (2024) describes “infinite learners” as those who ensure yesterday’s successes do not block tomorrow’s possibilities. Accessible education is not built by adding one more workshop on bias, but by repeatedly interrogating the habits that keep inequity comfortably in place.

Part of this interrogation is understanding the difference between integration and inclusion. As illustrated in the United Nations (2021) guidelines, integration occurs when students are expected to adapt themselves to fit into an existing system. Inclusion occurs when institutions change their structures, pedagogy, and assessments so that all learners can thrive. The connotations of “inclusion” are positive, while those of “integration” are often negative. These terms are not interchangeable.

The Vulnerability of Unlearning

Unlearning is a vulnerable act. Nović (2021) urges us to examine our everyday language and realize that common phrases like “to fall on deaf ears” or having “blind spots” use disability as a shorthand for negativity. McLeod et al. (2020) identify five principles for unlearning, beginning with the anticipation of discomfort.

If unlearning feels like a struggle, that is because it is. In cognitive neuroscience, unlearning is described as a deliberate form of cognitive rewiring: the active process of reshaping neural pathways to replace outdated mental models with new ones. Unlearning is often harder than learning because the brain is an efficiency machine. It naturally favors the path of least resistance, those deeply entrenched neural connections formed by years of repetition. Breaking these connections can cause physical discomfort or cognitive dissonance as the brain resists the energy cost of building new structures and adopting a new model which often feels physically exhausting or emotionally taxing (Kool et al., 2010).

However, the discomfort we feel is not a sign of failure, it is a sign of growth. It positions us as learners alongside our students. It asks us to inhabit what McWilliam calls “useful ignorance”: knowing what to do when we do not yet know what to do. This vulnerability connects to broader movements in decolonial and justice-oriented pedagogies which similarly emphasize the uncomfortable but necessary work of unlearning oppressive habits (Lopez, 2020).

An Invitation to Co-Create

As we celebrate the International Day of Education, I invite you to consider a few questions:

Which of our pedagogical beliefs might be past their expiration date?

Are we treating accessibility as a checklist or as co-creation with our students?

Do our assessments measure true learning, or do they reward speed and privilege?

The International Day of Education is often celebrated with stories of achievement. However, in an era shaped by disability justice and rapid technological change, the most urgent stories may be about what we are willing to stop doing. Unlearning offers a way to honor our commitment to inclusive, quality education while acknowledging how far we still have to go.

*The term “disabled” here is used intentionally to reflect both person-first (“person with a disability”) and identity-first (“disabled person”) language preferences, in line with Critical Disability Studies approaches (Campbell, 2009; Goodley, 2014).

references

Campbell, F. A. K. (2009). Contours of ableism: The production of disability and abledness. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230245181

Dalhousie University. (2025). Accessibility plan 2025-2028. https://www.dal.ca/content/dam/www/about/mission-vision-and-values/edia/accessibility-plan-2025-2028.pdf

Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9708722

Goodley, D. (2014). Disability studies: An interdisciplinary introduction (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Kool, W., McGuire, J. T., Rosen, Z. B., & Botvinick, M. M. (2010). Decision making and the avoidance of cognitive demand. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 139(4), 665–682. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020198

Lopez, A. E. (2020). Decolonizing the mind: Process of unlearning, relearning, rereading, and reframing for educational leaders. In Decolonizing educational leadership (pp. 57–83). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62380-7_4

McLeod, K., Thakchoe, S., Hunter, M. A., & Yano, S. E. (2020). Principles for a pedagogy of unlearning. Reflective Practice, 21(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1730782

McWilliam, E. (2005). Unlearning pedagogy. Journal of Learning Design, 1(1), 1-11. www.jld.qut.edu.au/Vol 1 No 1

Nović, S. (2021, April 5). The harmful ableist language you unknowingly use. BBC Worklife. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20210330-the-harmful-ableist-language-you-unknowingly-use

Price, D. (2021). Disability inclusive language guidelines: Annex II. United Nations Office at Geneva. https://www.ungeneva.org/en/about/accessibility/disability-inclusive-language/annex-ii

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2026). International Day of Education 2026 global event: The power of youth in co-creating education. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/international-day-education-2026-global-event-power-youth-co-creating-education

Yeh, C. (2024, January 29). Infinite learning: Why unlearning is the critical learning skill [Video]. TEDx Grandview Heights. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RB1zKxxYQLw