Transitioning Active Learning Methods Online in FASS, Part II

In the previous post, we covered how to quickly transition four common in-class activities to the online environment—while preserving each activity’s integrity—making use of the Dalhousie-approved video conferencing application, Collaborate Ultra, and our learning management system, Brightspace. Here are four more activities, plus, how to use them for an exam review.

Last time, we offered a note on accessibility and a “pro tip” to ensure smooth execution. They’re worth repeating here:

Note: The online active learning suggestions in this article assume that you’ve polled your class at the beginning of the course to determine students’ access to technology and digital resources. Assume that each student has variable access to the internet, a personal computer or even a smart phone. Asynchronous activities completed outside of class time are an empathetic acknowledgement of this reality, however, depending on your department or faculty, you may be required to do some synchronous (real-time) teaching. Activities are presented for both asynchronous and synchronous contexts.

Pro-tip: For synchronous learning, make sure you spend a few minutes explaining the features of the video conferencing app and how to use them by sharing your screen. Go through a quick test run. It will prevent chaos later.

Mind Mapping

A mind map (or spider web concept map [Centre, (n.d.)]) is an all-around neat tool for a variety of objectives—note taking, essay planning or exam review. Mind mapping’s strength lies in providing the student with a visual representation of main concepts, key terms, important people and dates, and the links among them. Mind mapping can be a solo activity or group one. There a several free online mind mapping tools, but much of the fun is drawing out the circles and lines oneself, not to mention the focus, retention and learner engagement benefits of the tactile experience.

Possible prep work: Create a template for students to fill out. The map is as simple as putting some circles and lines on paper, scanning it to your computer and then posting it to your Brightspace course site. Or, you might provide students with some specifications, like a set of key terms and a legend of symbols students should use to represent the linkages, then allow them to draw it themselves. Crayons, colored pencils and other art supplies fit right in with this activity. Students without a printer at home can upload the map into a Google Drawings file (in Google Drive), adding their own pictorial elements and notes digitally.

Synchronous: There are several ways to embed this activity during class time, depending on your goals and outcomes. You might ask students to organize their lecture notes in the map and pair students at the end of class so that partners can compare maps and help one another fill in gaps (use the map as a vehicle for the “note taking pairs” activity outlined below). Or, you might set aside time during lecture to put students into breakout groups and ask them to collaboratively fill out a digital template. Students use the annotation tools to draw squiggly lines, shapes and create text boxes (visit “session settings” to enable use of annotation tools by participants).

Provide students with the birds’ eye view of the lecture with a mind map—use the map in conjunction with lecture slides to display the organization of the lecture, sharing your own screen. Encourage students to replicate the map at home with coloured pencils, crayons and markers, adding in their own notes to the map. For many learners, engaging the hands increases focus and concentration—asking students to doodle on purpose might increase their engagement with and retention of lecture material (Andrade, 2010; Chick, 2014).

Asynchronous: Perhaps your course assessment includes reading reflection entries—you might consider asking students to turn in a mind map for one week’s readings. If you want to use the mind map as a vehicle for “note taking pairs,” for instance, follow the guidelines below, but ask students to work in Google Drive, using the “Google Drawings” file type.

Note Taking Pairs

This activity pairs up students in order that they may compare and strengthen each other’s lecture notes. Pair them up during class, after a natural break in your lecture, or after a lecture is complete. Student A shares the main ideas of the lecture, highlighting any confusion about concepts or noting sections that lack detail. Student B shares their understanding of the main points and assists partner A, clarifying concepts and filling in weak sections. The pairs switch roles for the next lecture section.

Synchronous: Assign pairs before the start of class (or randomly assign before the start of the activity) and use Collaborate’s breakout group feature when the time comes to pair up students. Set a timer. You might also combine this activity with the “Fish Bowl” from the previous post, collecting student questions about concepts anonymously, going over them at the end of class or at the start of the next.

Asynchronous: If you post video lectures on Brightspace, pair up students to compare and share notes on the discussion boards, giving them the start and stop timestamps of the lecture video sections for which you would like them to share notes (for example, “start at 1:01 and end at 6:41”). Alternatively, students could type their notes in Microsoft Teams, and collaboratively build notes there (Create a team for your entire class and then create subteams using Teams’ “hidden channel” feature).

Also, for an extra boost of engagement and to capture the deep learning that comes with talking out loud to others about new knowledge, use something like FlipGrid to have students share videos of themselves explaining a concept from their class notes.

Jigsaw Reading

This is another activity that binds students together in collaborative note construction, while being heavier on the peer teaching element. It requires two different groups: “collaborative” and “expert”. In the classroom, all students are divided into collaborative groups. Each member of the group is given a different reading. This might be one reading divided into sections, or entirely separate readings for each student. Students are given several minutes to read. After students complete their readings among their collaborative teammates, each student joins their expert group—groups composed of students who have read the same material. In the expert groups, students discuss the main points of the readings and how they might approach teaching the material to the others in their collaborative groups. After the set amount of time, the collaborative groups reform and each student “expert” presents the material from his or her section to the others. The end of class may be reserved for general discussion or eliciting questions from students about the readings.

Synchronous: As always, pre-assign the groups and readings and post them in Collaborative’s chat box or as an announcement in Brightspace. At the appointed time, tell each student to turn off their video cameras and microphones, allowing them some quiet time to read. When the timer you’ve set ends, Collaborate will alert students to come back to the group. Give the students instruction about what to do in their “expert” groups and then put each expert group into a breakout room, again setting a timer. Once they’re called back to the wider group, repeat the process, breaking students out into their “collaborative” groups. After time is up, you could use the Fish Bowl activity; resume the lecture hour; or pose more questions to the students to discuss in their collaborative groups, such as implications of the content in the readings, or to reflect on the experience of peer teaching—whatever suits the goals and outcomes of the course and lecture.

Asynchronous: One of the silver linings of asynchronous courses is that any activity, or element of an activity, could be stretched out over time, giving an opportunity to engage students in both the activity’s components and building the skills involved in those components. Give students in the expert group one week, for example, to prepare a “lesson plan” to teach the others. The slower pace of asynchronous courses may provide more time to build skills, such as synthesizing and teaching material, than might be possible in the ten minutes devoted to it in synchronous classes.

Simulations/Debates

A key pedagogical tool to develop students' academic and interpersonal skills, it may be hard to imagine transitioning simulations and debates to the online environment, given how dynamic and effervescent they can be in the classroom. However, each major component of a simulation can be effectively transitioned, and while the effervescence of student interaction and rhetoric may be subdued, the online version allows for a different experience that is just as worthwhile (Schiff, 2020). Jennifer Schiff, in a recent article on her “WRIS” system for political science simulations in the online classroom, offers a straight-forward organizational framework for instructors to design their simulations. The WRIS system is described below, followed by a “quick view” table matching each component with how-tos for Collaborate and Brightspace, and for synchronous and asynchronous contexts.

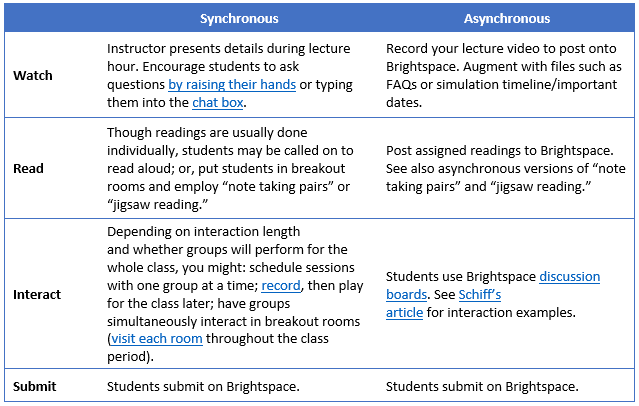

Schiff’s simulations are organized into these components: watch, read, interact, and submit. First, students watch a video of the instructor giving guidance and necessary background information for the topic and themes of the simulation. Students then read the required materials that present the concepts, terms and problems relevant to the interaction component. Students then interact with one another on discussion boards (or in video conferencing). They debate, negotiate, explain and persuade a treaty negotiation, a political referendum, a round-table discussion—whatever is appropriate for the course. Lastly, students complete an assignment to finish the WRIS cycle, submitting a short paper or a reflection, again, whatever best suits your course and assessment designs.

WRIS system quick view:

Exam Review Activities

Many of the activities presented in these two blog posts could serve as vehicles for exam review. The “Fishbowl” is a great method to anonymously collect questions and discuss them during the last class before the exam. Use “Think-Pair-Share" after giving students a set of sample exam questions so that they might work through them together or allow students to “mind map” a core concept as a brainstorming tool for exam essay questions. Encourage peer-to-peer teaching with “Jigsaw reading,” dividing students into expert and collaborative groups with the most relevant readings of the module, and then add this twist: have the expert groups create exam questions to pose to their peers in the collaborative group.

If you are unsure about how to transition a face-to-face activity that we have not covered in these posts, authors Green, Hamarman and McKee suggest asking yourself these questions:

(1) What are the specific elements and components that make the activity successful in person? (2) Can these elements and components be replicated online with minimal modification? (3) If not, what are the core goals and objectives of the original activity, and how else might they be accomplished online? (2015, p. 21)

We wish you good luck in transitioning face-to-face activities online! Consider sending us a tweet #DalOnline, sharing your own creative modifications during this time of mass collective transition. Keep checking this space as well for more articles and how-tos.

References

Andrade, J. (2010). What does doodling do? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24(1), 100-106.

Centre for Teaching Support and Innovation at the University of Toronto. (n.d.). Active learning and adaptive teaching techniques. Retrieved on April 30, 2020 from: https://teaching.utoronto.ca/teaching-support/active-learning-pedagogies/active-learning-adapting-techniques/note-taking-pairs/

Chick, N. (2014, January 22). Doodling & Knitting. Retrieved on May 9, 2020 from https://my.vanderbilt.edu/themindfulphd/2014/01/doodling-knitting/

Green, E.R., Hamarman, A., & McKee, R.W. (2015). Online sexuality education pedagogy: Translating five in-person teaching methods to online learning environments. Sex Education (15)1,19-30. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2014.942033