Unpacking the Research-Education Gap: A dialogue begun at the 2025 Dalhousie Conference on University Teaching and Learning

shawn xiong, phd

Instructor, Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

CLT Faculty Associate

I am worn out. I am an experienced educator, who, for the last 10 years, have been reading extensively in my field around disciplinary pedagogy and, more generally, in the teaching and learning literature. I try to keep up-to-date, incorporating findings from latest research as best I can, driven by an insecurity that my teaching practices will go stale, or will no longer reflect what is best for students in a constantly evolving teaching and learning landscape. I have engaged in collaborative scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) and discipline-based education research (DBER) projects across North America. Retrospectively, trying to stay relevant and sharp has worn me out—and is indicative of a prevalent issue in teaching, learning and educational research in higher education.

I have learned that my insecurity of becoming irrelevant is a manifestation of a more prevalent issue in Higher Education, known as the research-education gap, which refers to the disparity between what is known through research and what is implemented in teaching practices. When authors James, McKenna and Mishra (2024) describe the structural factors and constraints that create a chasm between researchers’ “cutting edge” findings and time-pressed educators never taught the fundamentals of course design, they say, “we feel there can be a reasonable discrepancy between when, and in what format, a topic is most relevant to researchers’ and educators’ day-to-day work. However, because of this, we have experienced implications that educators are “behind the times” or that researchers are “out of touch.”

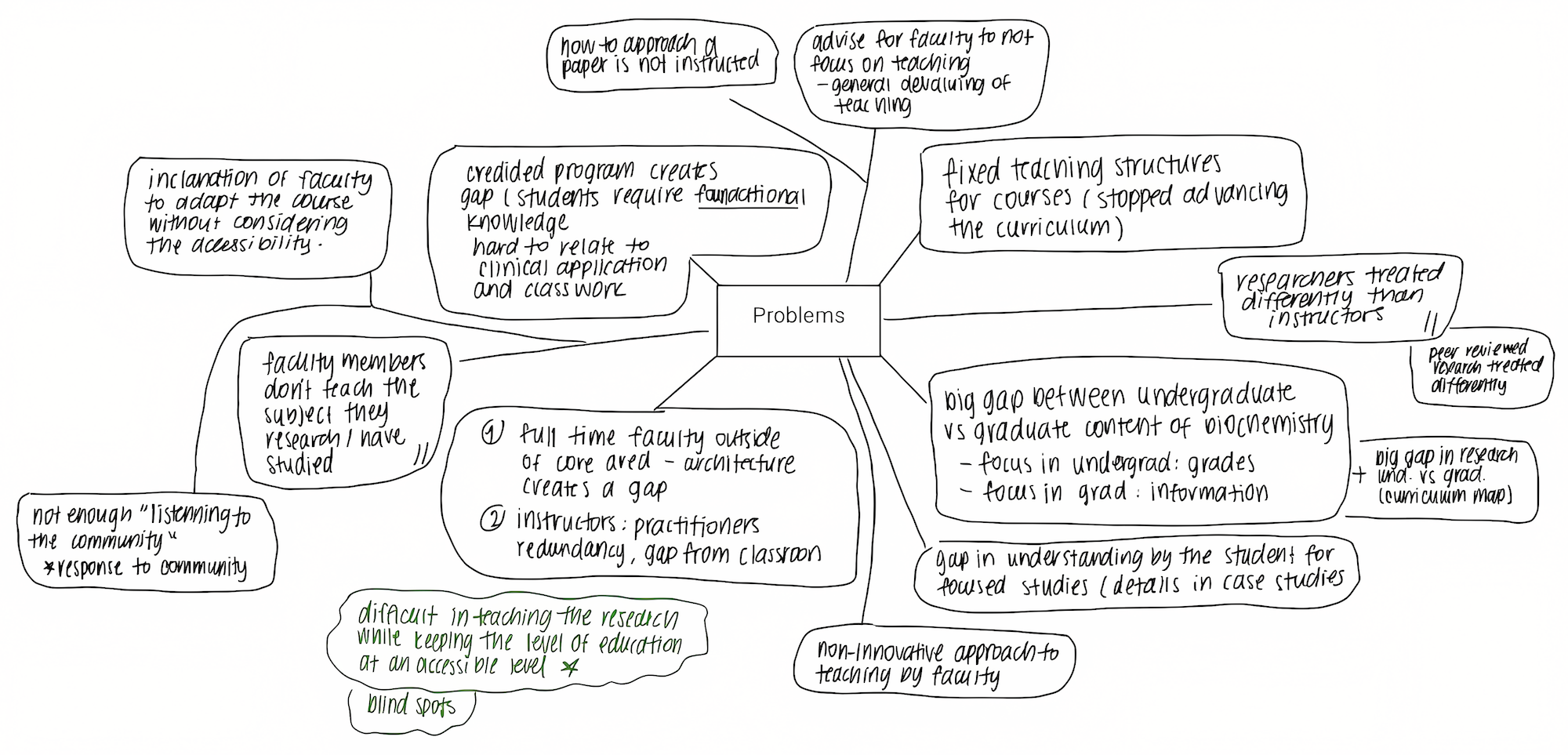

To unpack the research-education gap further, 18 participants gathered in a conversation circle at the 2025 Dalhousie Conference on University Teaching and Learning. Through our informative discussion, we identified many manifestations of the research-education gap, a summary of which is represented in the mind map created by Eda Ozsan:

Summary mind map

Five themes emerged from our conversation:

Inadequate alignment of undergraduate and graduate education

Difficulties in adapting and keeping fresh with the new research development as a generalist

SoTL (scholarship of teaching and learning) research is often viewed as less important or valuable than disciplinary research

The growing gaps between foundational training vs. specialty training

The gaps between community needs and community engaged learning/research

In the following paragraphs, I briefly discuss each theme and highlight the corresponding strategies and solutions discussed in our conversation circle.

Theme 1: Inadequate alignment of undergraduate and graduation education

This refers to the shock many new graduate students experience at the onset of their training, in which they find what they are about to study and research is nothing like how they have been taught as an undergraduate student. This may be especially true for STEM students, because what they learn in the classrooms and laboratories is often “behind the times” of the faculties’ own research.

To improve the alignment of undergraduate and graduate education, we need more than merely asking educators to stay current with their field and integrate novel research into their day-to-day teaching. Program-level planning and evaluation has been recommended to critically reflect on the compatibility of undergraduate courses offered with current disciplinary development. On the whole, the program should be willing to adjust once incompatibility is found to better align undergraduate training with current research development. For programs with laboratories and field courses, research skills—especially psychomotor skills—should be emphasized by adopting inquiry-based pedagogies, such as course-based undergraduate research experiences (CURE).

Theme 2: Difficulties in adapting and keeping apace with new research development as a generalist

This is felt by many educators who try their best to connect their students to real-world issues with what they are learning in their classrooms. This may be possible if one is teaching one upper year course in an area of one’s own research, but it quickly becomes impractical for educators who teach three or four courses per semester. One of the recommendations proposed during the conversation circle was to apply a jigsaw puzzle-based activity, in which students are assigned to learn about a recent advancement in the field related to class content, and then share what they learned within small groups. In this peer-to-peer teaching format, instructors are no longer the only one responsible for keeping the class up to date. It’s also important to balance the research content and the foundational teaching content, as alerted by one of our participants. When teaching introductory level classes, most of the students have yet to develop sufficient mastering of knowledge and skills to appreciate the cutting-edge research. If research is presented extensively and incongruently, students may feel confused and may be counter-productive for learning.

Theme 3: SoTL research is often viewed as less important or valuable than disciplinary research, especially in research-intensive universities

In part, this may be due to the relatively young status of SoTL as a research field since its establishment in the early 1990s. More importantly, one must not overlook structural factors that limit or sometimes prevent the popularization of SoTL as a legitimate and independent research field. Many institutions may not explicitly acknowledge SoTL as a valid form of research in their faculty handbooks or promotion/tenure guidelines, leading to a perceived (or actual) lack of institutional support and incentive. SoTL projects may not be eligible for the same funding sources as traditional disciplinary research, making it harder for faculty to secure resources for their work. Furthermore, many institutions lack adequate support for ethics approval of SoTL research, resulting in an overly complicated application process. Today, many teaching and learning centres offer small grants to support grassroot-level SoTL projects (see the CLT’s SoTL grant here [link opens in new page]).

To promote the awareness of, and gather support for SoTL, we may consider extending SoTL research to undergraduate students by increasing SoTL- and DBER-related course offerings at the undergraduate level; normalize SoTL and DBER representation at department seminars; and grow SoTL and DBER representation in summer research programs (James, et al., 2024).

Theme 4: The growing gap between foundational training vs. specialty training

This gap is especially notable for certified programs, such as those involved in health care. Several participants in the conversation circle commented that they are now spending more time to cover the foundational concepts that they had expected students to master before entering their specialty training. The consequence is less time devoted for professional and specialty training, resulting in less competent partitioners. Similarly, educators of the basic science program also see the same gap, manifested as unprepared students for upper year courses.

Part of the unpreparedness in our students may still be traced back to the impact of COVID-19 disruption, but more likely is the result of a misalignment between what is proposed to be assessed versus what is actually assessed. If a laboratory course has the objective to develop students’ psychomotor skills, then one would expect the psychomotor skills are assessed directly; however, this is rarely the case in practice. In addition, if a lecture course employs “specification grading” to promote students’ mastery of knowledge, then one should set the “specifications” higher than the passing level, to ensure the repeated attempts embedded to achieve the “specifications” are not rendered as a grade inflation mechanism. These two examples of misaligned learning objectives and outcomes represent not only a disservice to our students and our field, but also a missed opportunity for effective teaching and learning.

Theme 5: The gap between community needs and community engaged learning/research

Closing this gap is much needed, for two reasons:

The ongoing effort in decolonization compels us to seek out the knowledge holders in our communities and collaboratively solve issues inflicting local communities; and,

A volatile global economy due to unprecedented trading barriers and tariffs have conservatized governmental spending, resulting in increased scrutiny and accountability for university operating grants.

The latest Nova Scotia Auditor General’s report to the House of Assembly on Funding to Universities revealed a lack of accountability of how universities spend government funding. As a result, Nova Scotia Government has placed a restriction on $1.9 billion operating grants for universities over 5 years (Office, 2025). For instance, the Auditor General questioned the lack of evidence on how the nearly $200 million in health education grants have helped the expansion of nursing programs. Likewise, Nova Scotians who paid for the university operating grants are equally eager to know “How does the Department of Advanced Education plan to hold universities accountable for the public funds they receive?”

This series of moves from the release of Auditor General’s report to the recent accountability act of the provincial government to withhold portion of the university operating grants could be easily interpreted as a top-down interference to university’s freedom of research, but it could also be perceived as the desperate needs of our local communities for help and innovation from universities during this unprecedented global turbulence. While universities become more accountable by assessing and meeting the grants’ goals periodically, it’s recommended that we as university educators could consider adopting placed-based pedagogies and service learning-based pedagogies to connect our students to the land we are on and attend to the needs of the local communities, to better fulfill Dalhousie’s institutional strategic plan on impactful community engagement.

The research-education gap is metamorphic, manifesting in all kinds of shapes and forms. In a more recent conversation focused on science education, Dr. Alison Thompson from the Department of Chemistry skillfully illustrated her struggle in addressing the research-education gap as aiming to help pupils to read stories (research in chemistry) while we only teach them alphabets (education in chemistry). This metaphor captures the heart of the challenge: without bridging the gap, we risk leaving students fluent in isolated facts but illiterate in the broader narratives that give those facts meaning. To move forward, we must reimagine education not as a linear transmission of knowledge, but as a dynamic dialogue between research and practice. Closing the research-education gap is not a one-time fix, but rather a continuous process of translation, collaboration, and reflection.

References

James, N. M., McKenna, M. S., & Mishra, A. (2024). Toward collaborative Dialogue: Unpacking the Researcher–Educator divide to advance chemistry education. Journal of Chemical Education, 101 (8), 2960–2965. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.3c01321

Office of the Auditor General of Nova Scotia. (2025, March). Funding to universities. https://www.oag-ns.ca/audit-reports/funding-universities